We will now prove the structure theorem for finitely generated abelian

groups, since it will be crucial for much of what we will do later.

Let

denote the ring of integers, and

for each positive integer

denote the ring of integers, and

for each positive integer  let

let

denote the ring of integers

modulo

denote the ring of integers

modulo  , which is a cyclic abelian group of order

, which is a cyclic abelian group of order  under

addition.

under

addition.

Definition 3.0.1 (Finitely Generated)

A group

is

if there exists

such that every element of

can be obtained from the

.

We will prove the theorem as follows. We first remark that any

subgroup of a finitely generated free abelian group is finitely

generated. Then we see that finitely generated abelian groups can be

presented as quotients of finite rank free abelian groups, and such a

presentation can be reinterpreted in terms of matrices over the

integers. Next we describe how to use row and column operations over

the integers to show that every matrix over the integers is equivalent

to one in a canonical diagonal form, called the Smith normal form. We

obtain a proof of the theorem by reinterpreting in

terms of groups.

Proposition 3.0.3

Suppose  is a free abelian group of finite rank

is a free abelian group of finite rank  , and

, and  is a

subgroup of

is a

subgroup of  . Then

. Then  is a free abelian group generated by at

most

is a free abelian group generated by at

most  elements.

elements.

The key reason that this is true is that  is a finitely generated

module over the principal ideal domain

is a finitely generated

module over the principal ideal domain

. We will give a complete

proof of a beautiful generalization of this result in the context of

Noetherian rings next time, but will not prove this proposition here.

. We will give a complete

proof of a beautiful generalization of this result in the context of

Noetherian rings next time, but will not prove this proposition here.

Corollary 3.0.4

Suppose  is a finitely generated abelian group. Then there are

finitely generated free abelian groups

is a finitely generated abelian group. Then there are

finitely generated free abelian groups  and

and  such that

such that

.

.

Proof.

Let

be generators for

. Let

and let

be the map that sends the

th generator

of

to

. Then

is

a surjective homomorphism, and by Proposition

3.0.4 the

kernel

of

is a finitely generated free abelian group.

This proves the corollary.

Suppose  is a nonzero finitely generated abelian group. By the

corollary, there are free abelian groups

is a nonzero finitely generated abelian group. By the

corollary, there are free abelian groups  and

and  such that

such that

. Choosing a basis for

. Choosing a basis for  , we obtain an

isomorphism

, we obtain an

isomorphism

, for some positive integer

, for some positive integer  . By

Proposition 3.0.4,

. By

Proposition 3.0.4,

, for some integer

, for some integer  with

with

, and the inclusion map

, and the inclusion map

induces a map

induces a map

. This homomorphism is left

multiplication by the

. This homomorphism is left

multiplication by the  matrix

matrix  whose columns are the

images of the generators of

whose columns are the

images of the generators of  in

in

. The of

this homomorphism is the quotient of

. The of

this homomorphism is the quotient of

by the image of

by the image of  , and the

cokernel is isomorphic to

, and the

cokernel is isomorphic to  . By augmenting

. By augmenting  with zero columns on

the right we obtain a square

with zero columns on

the right we obtain a square  matrix

matrix  with the same

cokernel. The following proposition implies that we may choose bases

such that the matrix

with the same

cokernel. The following proposition implies that we may choose bases

such that the matrix  is diagonal, and then the structure of

the cokernel of

is diagonal, and then the structure of

the cokernel of  will be easy to understand.

will be easy to understand.

We will see in the proof of Theorem 3.0.3 that

is uniquely determined by

is uniquely determined by  .

.

Proof.

The matrix

will be a product of matrices that define elementary

row operations and

will be a product corresponding to elementary

column operations. The elementary operations are:

- Add an integer multiple of one row to another (or a multiple

of one column to another).

- Interchange two rows or two columns.

- Multiply a row by

.

.

Each of these operations is given by left or right multiplying by an

invertible matrix

with integer entries, where

is the result of

applying the given operation to the identity matrix, and

is

invertible because each operation can be reversed using another row or

column operation over the integers.

To see that the proposition must be true, assume  and perform

the following steps (compare [Art91, pg. 459]):

and perform

the following steps (compare [Art91, pg. 459]):

- By permuting rows and columns, move a nonzero entry of

with

smallest absolute value to the upper left corner of

with

smallest absolute value to the upper left corner of  . Now attempt

to make all other entries in the first row and column 0 by adding

multiples of row or column 1 to other rows (see step 2 below). If an

operation produces a nonzero entry in the matrix with absolute value

smaller than

. Now attempt

to make all other entries in the first row and column 0 by adding

multiples of row or column 1 to other rows (see step 2 below). If an

operation produces a nonzero entry in the matrix with absolute value

smaller than  , start the process over by permuting rows and

columns to move that entry to the upper left corner of

, start the process over by permuting rows and

columns to move that entry to the upper left corner of  . Since the

integers

. Since the

integers  are a decreasing sequence of positive integers, we

will not have to move an entry to the upper left corner infinitely

often.

are a decreasing sequence of positive integers, we

will not have to move an entry to the upper left corner infinitely

often.

- Suppose

is a nonzero entry in the first column, with

is a nonzero entry in the first column, with

. Using the division algorithm, write

. Using the division algorithm, write

,

with

,

with

. Now add

. Now add  times the first row to the

times the first row to the

th row. If

th row. If  , then go to step 1 (so that an entry with

absolute value at most

, then go to step 1 (so that an entry with

absolute value at most  is the upper left corner). Since we will

only perform step 1 finitely many times, we may assume

is the upper left corner). Since we will

only perform step 1 finitely many times, we may assume  .

Repeating this procedure we set all entries in the first column

(except

.

Repeating this procedure we set all entries in the first column

(except  ) to 0. A similar process using column operations

sets each entry in the first row (except

) to 0. A similar process using column operations

sets each entry in the first row (except  ) to 0.

) to 0.

- We may now assume that

is the only nonzero entry in the

first row and column. If some entry

is the only nonzero entry in the

first row and column. If some entry  of

of  is not divisible

by

is not divisible

by  , add the column of

, add the column of  containing

containing  to the first

column, thus producing an entry in the first column that is nonzero.

When we perform step 2, the remainder

to the first

column, thus producing an entry in the first column that is nonzero.

When we perform step 2, the remainder  will be greater than 0.

Permuting rows and columns results in a smaller

will be greater than 0.

Permuting rows and columns results in a smaller  . Since

. Since

can only shrink finitely many times, eventually we will get

to a point where every

can only shrink finitely many times, eventually we will get

to a point where every  is divisible by

is divisible by  . If

. If  is negative, multiple the first row by

is negative, multiple the first row by  .

.

After performing the above operations, the first row and column

of

are zero except for

which is positive and divides

all other entries of

. We repeat the above steps for the

matrix

obtained from

by deleting the first row and column.

The upper left entry of the resulting matrix will be divisible by

, since every entry of

is. Repeating the argument

inductively proves the proposition.

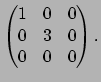

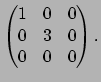

Example 3.0.6

The matrix

is equivalent

to

and the matrix

is equivalent to

Note that the determinants match, up to sign.

Proof.

[Theorem

3.0.3]

Suppose

is a finitely generated abelian group, which we may assume

is nonzero. As in the paragraph before Proposition

3.0.6,

we use Corollary

3.0.5 to write

as a the cokernel

of an

integer matrix

. By Proposition

3.0.6

there are isomorphisms

and

such that

is a diagonal matrix with entries

, where

and

. Then

is isomorphic to the cokernel of the diagonal matrix

, so

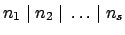

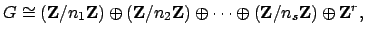

|

(3.1) |

as claimed. The

are determined by

, because

is the

smallest positive integer

such that

requires at most

generators (we see from the representation (

3.0.1) of

as

a product that

has this property and that no smaller positive

integer does).

William Stein

2004-05-06

![]() denote the ring of integers, and

for each positive integer

denote the ring of integers, and

for each positive integer ![]() let

let

![]() denote the ring of integers

modulo

denote the ring of integers

modulo ![]() , which is a cyclic abelian group of order

, which is a cyclic abelian group of order ![]() under

addition.

under

addition.

![]() is a nonzero finitely generated abelian group. By the

corollary, there are free abelian groups

is a nonzero finitely generated abelian group. By the

corollary, there are free abelian groups ![]() and

and ![]() such that

such that

![]() . Choosing a basis for

. Choosing a basis for ![]() , we obtain an

isomorphism

, we obtain an

isomorphism

![]() , for some positive integer

, for some positive integer ![]() . By

Proposition 3.0.4,

. By

Proposition 3.0.4,

![]() , for some integer

, for some integer ![]() with

with

![]() , and the inclusion map

, and the inclusion map

![]() induces a map

induces a map

![]() . This homomorphism is left

multiplication by the

. This homomorphism is left

multiplication by the ![]() matrix

matrix ![]() whose columns are the

images of the generators of

whose columns are the

images of the generators of ![]() in

in

![]() . The of

this homomorphism is the quotient of

. The of

this homomorphism is the quotient of

![]() by the image of

by the image of ![]() , and the

cokernel is isomorphic to

, and the

cokernel is isomorphic to ![]() . By augmenting

. By augmenting ![]() with zero columns on

the right we obtain a square

with zero columns on

the right we obtain a square ![]() matrix

matrix ![]() with the same

cokernel. The following proposition implies that we may choose bases

such that the matrix

with the same

cokernel. The following proposition implies that we may choose bases

such that the matrix ![]() is diagonal, and then the structure of

the cokernel of

is diagonal, and then the structure of

the cokernel of ![]() will be easy to understand.

will be easy to understand.

![]() and perform

the following steps (compare [Art91, pg. 459]):

and perform

the following steps (compare [Art91, pg. 459]):

is equivalent

to

is equivalent

to

and the matrix

and the matrix

is equivalent to

is equivalent to

Note that the determinants match, up to sign.

Note that the determinants match, up to sign.![]()